This tribute to Salif Keita is long overdue. I first met this great Malian musician in Ségou, a regional capital city in south-central Mali in the early 1980s. With a big band of more than 20 musicians, Salif Keita performed in the open air court of a second-rate hotel in the outskirts of this modest city. It was a hot, humid Saturday night in August, 1984. We were in the middle of the rainy season. I was struck by the versatility of his music: African, Caribbean, Latin American, jazzy. He captivated the audience, all music lovers from Mali. I was the only white person in the crowd. From that day on, I was a passionate fan of this allround musician and singer.

I was also very much impressed by Salif Keita’s modesty. Greeting ceremonies in Mali are complicated and lengthy. One day, in the late 1980s, I was standing next to the reception desk in the lobby of (then) one of Mali’s most luxurious hotels – Hotel de l’Amitié in Bamako, the country’s capital – waiting for an appointment who was late. It was around 7:30 a.m. I saw Salif Keita stepping out of the elevator, walking towards the reception desk and greeting everyone behind the desk . When he was done he continued greeting the by-standers, including me. He took his time, he greeted everybody as if they were his brothers and sisters. Maybe they were, because in Mali many people are related – somehow, somewhere.

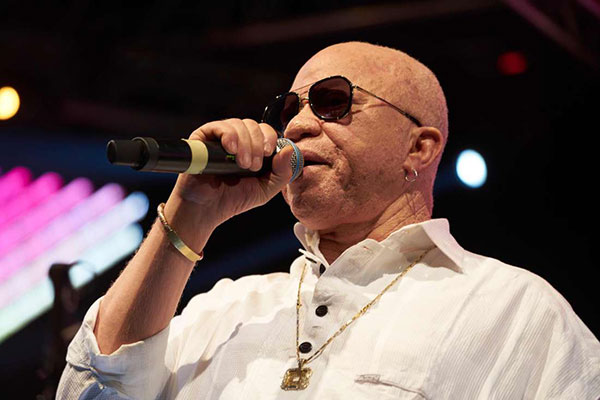

The third time I came face to face with Salif Keita was at the Africa festival in Hertme, the Netherlands, in 2013. Salif had become a middle-aged gentleman in his sixties, slightly corpulent, but his music was as brilliant as ever!

Salif Keita’s star will continue to shine, also after this retirement. As a person with albinism he has realized one of the most envied goals one can imagine. Millions have enjoyed his music – and still do. He is world famous. In the future he will continue to raise his voice against the discrimination of people living with albinism, against the murder and mutilation of innocent people, men, women, children, even babies who are being victimized because of their albinism. His last public performance was at a free concert on November 17 in Fana, in Mali, dedicated to the memory of Ramata Diarra, a five-year-old girl with albinism who was brutally murdered then mutilated in a ritual killing in May of this year. It will certainly not be the last time we’ve heard of Salif Keita. His struggle is our struggle. A luta continua!

(webmaster FVDK)

Salif Keita retires, his Golden Voice falls silent

Published: November 24, 2018

By: Charles Onyango-Obbo

The great Malian musician Salif Keita, dubbed the “Golden Voice of Africa,” has announced his retirement from performing.

The 69-year-old Keita made the announcement after the release of, supposedly, the last album of his storied career. Titled Another White, it is a cry for the protection of people with albinism, a cause he has championed all his life.

Born into a local royal house, Keita was rejected by his family because of his albinism, considered either a sign of bad luck in many African cultures – or mysterious power, which drives the ritual killing of people with albinism.

In East Africa, Tanzania and Burundi are notoriously dangerous places to be a person with albinism.

Appropriately, Keita gave what could be his last major public performance at a free concert on November 17 in the town of Fana, in Mali, dedicated to the memory of Ramata Diarra, a five-year-old boy living with albinism who brutally murdered then mutilated in a ritual killing early in the year.

I am one of those Africans for whom Keita offered one of the defining sounds of our youthful years. There is something unique about Keita’s generation of musicians, along with other luminaries like Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango, and Guinea’s Mory Kante, and on the more youthful end, Senegal’s Youssou N’dour, to name a few.

First, their music isn’t always overtly political, though it is. They sing in their native tongues, and draw heavily from folk imagery, local culture, history, and communal stories.

Probably as a result of that, they function like mediums, so bring a great ease to their art. It is almost annoying.

Some years ago, at an Africa arts festival in Copenhagen, over the course of a week I watched performances by Keita, N’dour, and Malian kora player Toumani Diabate one after another.

They mesmerised the crowds but Keita and Diabate especially barely broke a sweat. It was as if they could have still have pulled it off even if they were half asleep.

That was in stark contrast to watching the performances of Hugh Masekela or Fela Kuti, some of the most political musicians to have come out of Africa.

They laid into their music and its politics with incredible energy and fury that left you giddy with revolutionary spirit. Going to the street to protest oppression or the bush to join the rebellion, seemed to be the next logical step.

But it’s in that contrast that the music of Keita and others in his musical tribe reveals their relationship to the broader African liberation experience.

In the Cold War era, when music often ran into ideological walls, and the troubled 1970s and 1980s in Africa, Masekela and Kuti played to an internationalist solidarity crowd that had bought into the anti-apartheid and anti-imperialist movements, were angry at the World Order, and wanted to overthrow it.

People like Keita won over the fence-sitters, the ignorant, the soccer moms, and people of goodwill. They didn’t fit the stereotype of flame-throwing radicals, and thus lowered the cost of embracing progressive African causes in a polarised world.

Closer home, The Man, Congolese great Franco Luambo Makiadi, had a similar effortless genius.

One of the most accomplished musicians Africa will ever produce, on stage his massive figure seemed a strangely reluctant presence – until he opened his mouth and moved his guitar fingers.

Charles Onyango-Obbo is publisher of data visualiser Africapaedia and Rogue Chiefs. Twitter@cobbo3

Source: Salif Keita retires, his Golden Voice falls silent