The case presented here is not a recent one. It relates to the year 2000. A young boy, Brima Kposowa, had been missing for several days from the village of Temede in Bumpeh District, Sierra Leone. His mutilated body was found after an apparently intensive search in early May 2000. A number of suspects was soon arrested, but the subsequent investigation and trial of the accused raise many questions.

Dr. Lans Gberie has been studying the case, as part of an ongoing research into ritual killings. In Dr. Gberie’s own words: “(…) I recently read the trial records of this case, known as ‘Abubakar Kallon vs. the State’. Meticulously bound, they run to 193 pages: consisting of the transcripts of police statements taken, court testimonies, a so-called forensic report, the Judge’s summing up for the juries and Foremen, and the verdict and sentencing statement. The trial appeared to have followed all the formal rules of such proceedings; it certainly was ponderous. But it is hard to say that it was fair.”

For this reason I present his findings and conclusions here. Maintaining ‘the rule of law’ also implies a fair trial. Please judge for yourself whether this has been the case here. It is a lengthy article but certainly worth reading. (webmaster FVDK)

A Killing, A Torture & A Death Sentence For Ritual Murder

By Dr. Lans Gberie

Article in Global Times – Sierra Leone by Amadu Daramy

Published on May 16, 2018

Alhaji Bockarie Kallon was sentenced to ‘suffer death’ by the circuit court sitting in Bo on 24 August 2002. He was 70. Mr. Kallon had been convicted of murdering, for ritual purposes, a 9-year old boy, Brima Kposowa, two years earlier. Judge Olu Ademusu, presiding, noted, apropos of the severity of the crime and the death sentence, that ritual killing was “becoming rampant” in Sierra Leone. “The sentence of the court upon you,” Mr. Ademusu told Mr. Kallon, “is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison, and thence to a place of execution, and that you there suffer death by hanging until you are dead. And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

Mr. Kallon was then taken to Pademba Road Prison and gaoled; I have found no record anywhere of what happened to him next. He might have died forgotten in the prison shortly after (he was 70), as so many condemned prisoners have; but he almost certainly was not hanged.

As part of an ongoing research into ritual killings, I recently read the trial records of this case, known as ‘Abubakar Kallon vs. the State’. Meticulously bound, they run to 193 pages: consisting of the transcripts of police statements taken, court testimonies, a so-called forensic report, the Judge’s summing up for the juries and Foremen, and the verdict and sentencing statement. The trial appeared to have followed all the formal rules of such proceedings; it certainly was ponderous. But it is hard to say that it was fair.

The police report containing the statements of several accused persons upon which the case was built were obtained through torture of almost medieval severity; the doctor who did the ‘forensic examination’ was not a pathologist and his report was inept and ridiculous; and the involvement of certain powerful local forces who were certainly not beyond suspicion with respect to their culpability in the crime raises the probability of a mistrial.

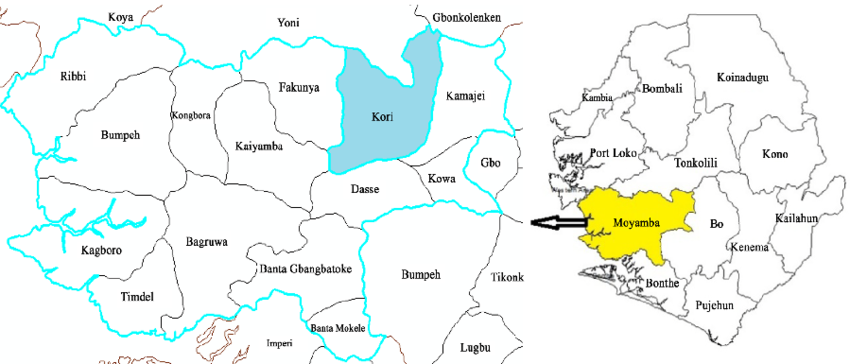

Context

The context of the trial is of more than incidental interest. The body of young Brima Kposowa, who had been missing for several days from the village of Temede in Bumpeh District, was found after an apparently intensive search in early May 2000. At almost exactly this moment, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels had abducted 300 United Nations peacekeepers and killed some, triggering a massive crisis for the UN’s budding peace operation in Sierra Leone. The Kamajors, then a very powerful pro-government force combating the RUF, was active in the Temede area. Their spiritual leader, Alieu Kondewa, appears in the pages of the trial records; he and the local chief ordered the Kamajors to apprehend four people in connection to the disappearance; they arrested those four people even before the body was found. They four were taken to a police station in Bo. The Bo police, under Karrow Kamara, then despatched a team to the village to search for the missing boy. The police team joined the Kamajors in this search. The body was found in a swamp some distance away from the village: it had not been hidden or buried, suggesting that if it was murder there was no real attempt at cover up.

The police then brought Dr. Brima Kargbo, a senior medical officer attached to the Bo Government Hospital, to examine the body where it had been found. This was on 5 May. He was not a pathologist. His report, tendered to the court as Exhibit A, is confusing: it outrages chronology and sequencing, not to mention probability. He said he found the body “lying and almost decomposing”, and that he conducted the examination on the spot. “Looking at the corpse I did not see the head,” he said. Upon further search, he said, “we found the head under a shrub about two to three yards from where the deceased was lying.” The search party had to wait for the doctor to look for the head? Though the body was decomposing, Dr. Kargbo’s report does not mention that it was smelling, something that surely would have led the search party earlier to the head, which must have been similarly decomposing. The body appeared to have been purposively decapitated: “the heart and liver were not seen,” Dr. Kargbo said.

Borfina

In one of his statements – which he later recanted in court because he claimed, credibly, that it had been extracted from him through torture – Mr. Kallon had claimed that he had removed those body parts after killing Kposowa to take to Guinea, there to be used by some unnamed ‘Meresin’ men to make ‘borfina’. This ‘borfina’, a powerful concoction, would have aided him in his quest to become a Paramount Chief.

The word ‘borfina’ is massively resonant in the literature relating to the Human Leopard phenomenon: it entered the popular imagination after the British colonial authorities set up a special commission court to try several dozen cases relating to mysterious killings attributed to ‘human leopards’ in 1912. Sir William Brandford Griffith, a former governor of the Gold Coast, was summoned from his retirement in London to preside over the commission. He described the ‘borfina’ as “a terrible fetish” which must be “frequently supplied with human fat” to remain potent. He later ventured the opinion that the incidental uses of human flesh by the Human Leopards was not “to satisfy any craving for human flesh nor in connection with any religious rite, but in the belief that the victims’ flesh will increase their virility.” He drew this conclusion from the fact that “all the principal offenders were men of mature age, past their prime.”

I shall return to the Griffith commission, his fatuous opinion, and the details of what was almost certainly a terrible mistrial that led to the hanging of a large number of perfectly innocent men during a moment of colonial hysteria. Griffith won international renown as a champion of Western civilization in one of the barbarous corners of the world for this trial; it earned him obituary notices in the Times of London and the New York Timesupon his death.

In Mr. Kallon’s trial, several people, including the parents of Kposowa, were charged with being accessory to the murder of the boy. Karrow Kamara, who was then officer in charge at the Bo Police Station, was the chief statement taker. He emerges from the pages of the trial records as a vicious torturer of demented cruelty. His preferred method was to use a plier, a club, and other blunt heavy instruments to beat up witnesses and the accused; he had the ear of one witness sliced off; he put out fire from cigarettes on their faces; and he had the mother and aunt of Kposowa so severely beaten that they bled through their genitalia, in which he then inserted a cocktail of meshed pepper – causing such pain, the aunt said, that it reminded her of when she was circumcised…

(To be continued)

A Killing, Torture & A Death Sentence For Ritual Murder (Part II)

By Dr. Lans Gberie

Article in Global Times – Sierra Leone by Amadu Daramy

Published on May 17, 2018

The State Counsel, Monfred Sesay, charged a total of nine people in connection with the alleged killing. They were Alhaji Abu Bockarie Kallon, for murder; Gassimu Ndanema, Francis Leigh, Abdulai Lamboi, Alhaji Sam, Joseph Sandy, Munda Alfred, Amie Dauda (mother of the deceased), and Mamie James (aunt of the deceased) as accessories to the crime of murder. The nine individuals, the indictment ran, “on 17 April 2000…conspired together with other persons unknown to commit a felony” in the judicial district of Bo.

The evidentiary exhibits upon which the indictment drew were mainly confessions; the accused seemed to condemn themselves with their own mouths. In fact, the so-called confessions, extracted through savage torture, were of an extremely dubious probative value. It is hard to believe, reading those statements, that any lawyer would have used them to make such grave charges: they are very obviously contrived. Here, for example, is how Amie Dauda, the mother of the deceased, described her own role in the murder (to her torturer Karrow Kamara): “The death of my son, Brima Kposowa, was not a natural death. It was caused by five of us, namely myself Amie Kposowa, Jose Sandy, Muda Alfred… We sold Brima Kposowa to one Alhaji Gassimu of Bo.”

Mr. Kallon, the first accused, in his first statement to the police on 4 May 2000 denied any knowledge of the killing. Several hours with the torturer Karrow Kamara the next day, 5 May, produced the following statement: “I now say that I have knowledge about the death of Brima Kposowa…I now say that I killed the deceased…on 17th April 2000 in a swamp, at Timiday bush at about 6:30pm. I alone did the killing…I now say that I have a right to stand for Paramount Chief at Koya Chiefdom…as I hailed from a ruling families [sic].” As part of his preparation to contest for Paramount Chief, Mr. Kallon, described as businessman, said he consulted “co-suspect Gassimu Ndanema,” telling Ndanema that in order to be successful in this endeavour, he must protect himself “by offering human sacrifice to wash” his body, according to the testimony.

To acquire the human being for the sacrifice, Mr. Kallon said he gave Danema Le.300,000 to purchase a boy, money Mr. Nanema used to purchase Brima Kposowa from his parents. The amount of money paid for the boy changed several times during the trial, from Le.300,000 to Le.600,000 and finally Le.800,000. Once bought, Ndanema gave the boy to Mr. Kallon, and drove them away from the village. Mr. Kallon then took the boy, alone, into a swampy area in the bush and – Mr. Kallon’s testimony read – “I laid him flat on the grass and offered my sacrifice…wherein I read ‘Al-Fatiah’ on the said Brima Kposowa five times and thereafter I had to use my knife to cut his throat and in the exercise the head of Brima Kposowa cut off.” He had not wanted to decapitate Kposowa, so he threw the head away. He then slit Kposowa’s stomach and extracted the liver and then “collected some of [Kposowa’s] blood in a red plastic.” He was to take the body part and blood to Labbeh in Guinea for the making of ‘borfina’. In the event, Mr. Kallon said in his testimony, he did not get anywhere near Guinea, because the plastic bag containing the ‘sacrifice’ got burst, spilling its prized content. Mr. Kallon said he got disoriented after this loss, “and this obliged me to give a false statement to the Police.”

The knife with which Mr. Kallon claimed he slaughtered Kposowa, which he described in precise terms, was never found – much like the British were never able to apprehend, after dozens of arrests, the exactly described forked knives allegedly used by Human Leopards. Where the liver and blood got wasted was never identified; Mr. Kallon did not seem to remember such an immensely striking detail. In Mr. Ndanema’s testimony, the decomposing body of Kposowa described by Dr. Kargbo became “skulls”. Amie Dauda did not state how much money she received. Another salient fact is that all the accused were not literate in English, and the statements were taken from them in either Mende or Krio and rendered in English by Karrow Kamara and his co-torturers.

Under cross-examination by the defence, an immensely salient detail emerged from Amie Dauda’s (mother of the deceased). In the morning that her son disappeared, she was home with the boy when he went behind the house “to the toilet.” Shortly after, she said Alieu Kondewa, the Kamajors spiritual leader, drove by the house. “As the vehicle passed, I did not see the child again,” she said. She went in search of the boy and never found him, whereupon she reported the matter to the local authorities, the most powerful of whom were Kamajors. They immediately had her tied “with a Kamajors rope called Baime” and beat her mercilessly. She and others arrested that day were taken to the Bo Police Station where Karrow Kamara “inserted pepper in my vagina.” It was then that “I admitted it was my doing, because the pepper was burning…. It was Karrow Kamara who suggested to me that I sold the child and which is not true.” She acquiesced with Kamara’s accusation, she said, “because of the burning pepper and this was what the police read to me.”

Her sister and co-accused, Mamie, was similarly tortured to ‘confess’ to doing what Karrow Kamara, acting in concert with the local authorities and the Kamajors, wanted her to confess to. “Mr. Karrow Kamara had a rubber with which he was flogging me,” she during her cross-examination. “[Police] Sergeant Gaima came to the scene. He slapped me in my mouth causing one of my teeth to come out.” The torturers then kicked her in the abdomen and “I started bleeding until I lost consciousness,” she said. Once she regained consciousness, they “inserted kanya pepper into my vagina. After that I was unable to walk. I was,” she said, evoking what to her must have been her primal experience of terror, “I was feeling like somebody who had been circumcised.”

Judge Ademusu, summing up for the jury, ignored these statements. He focused on Mr. Kallon who, he said, told the jury that “he was tortured and beaten by OC Karrow Kamara at the scene” of the murder (untrue: Mr. Kallon said he was beaten at the Police Station). However, Ademusu continued, the evidence of Dr. Kargbo, who played the role of pathologist though he had no such qualification, in his “post mortem examination report shows that the first accused’s indirectly made the confession.” Needless to say, it wasn’t Dr. Kargbo’s job to extract any confession, direct or indirect, from the accused.

The jury convicted Mr. Kallon of first-degree murder; and the judge sentenced him to death. The jury found the rest (8 accused persons) Not Guilty of the crime of accessory to the murder, and the judge had them freed.

Nothing in the records of the case prepared me enough for this curious verdict.

Article by Dr. Lans Gberie

Source: Global Times – Sierra Leone

A Killing, A Torture & A Death Sentence For Ritual Murder

Published May16, 2018

A Killing, A Torture & A Death Sentence For Ritual Murder (Parrt II)

Published May 17, 2018