On June 4, this year, I drew attention to Spirit Child, a film on infanticide in West Africa, made by Anas Aremeyaw Anas and Seamus Mirodan, and I reproduced a related article, published by Al Jazeera. The article, on infanticide in Ghana – and Burkina Faso, Benin and Nigeria – was a follow-up to a 2013 investigative report of the same journalist and filmmaker, Anas Aremeyaw Anas. The latter and his colleague, Seamus Mirodan, are to be commended for their fight against infanticide.

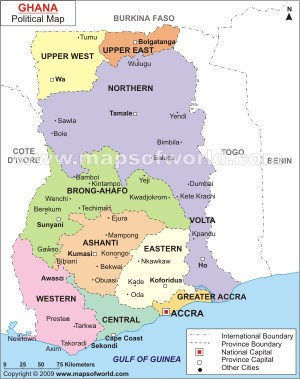

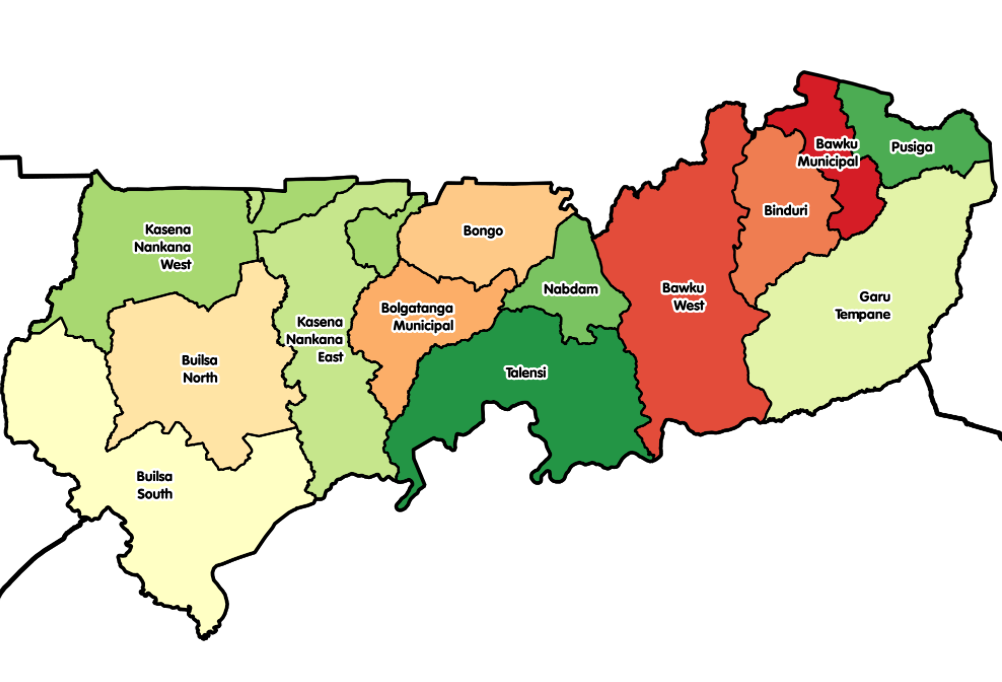

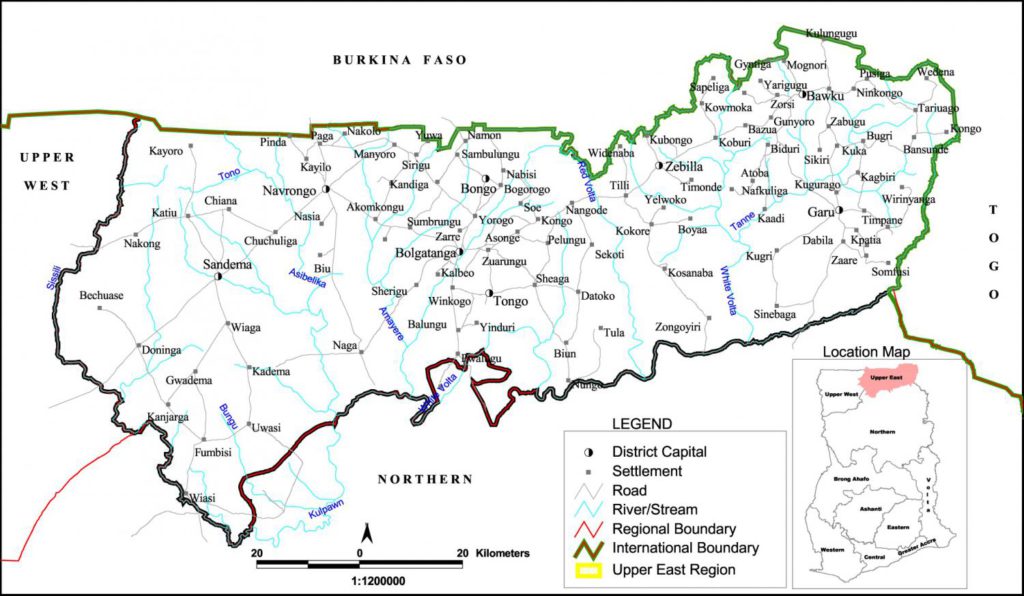

Fortunately, they are not the only ones who raise there voices against these age-old practices which have no reason to exist in the 21st century. While mentioning the names of others it is not my intention to belittle the activities and achievements of others, who work with them. Recently, I read an article on AfriKids, a non-governmental organization running an orphanage in northern Ghana, in the Upper East Region, in a village called Sirigu, to be more specific. Project manager at AfriKids is Joseph Asakibeem, who was recently awarded the Bond Humanitarian Award 2018 for his work in saving many children who would have been killed due to the gruesome traditional practice of killing disabled children and so-called ‘spirit childs’. More on Afrikids and its work in my next post.

When reading about the village of Sirigu I remembered an article, written by another outstanding Ghanaian journalist, Seth Kwame Boateng. In 2011 he visited Sirigu and made a breath-taking documentary for Ghana’s Joy 99.7 FM’s Hotline. Below the transcript.

Seth Kwame Boateng was named ‘journalist of the month‘ in July 2017 and can boast of an impressive list of awards and documentaries. Read here what he wrote in 2011 on infanticide in Northern Ghana. (webmaster FVDK)

SHOCKING!…Ritual baby killing in Northern Ghana

Originally published on April 1, 2011

by Seth Kwame Boateng

Joy FM reporter Seth Kwame Boateng visits an orphanage in the Upper East Region of Ghana called “Sirigu” to uncover the chilling practice of cultural murder; the killing of babies who are born with deformities, or whose birth coincide with a tragic incident in the family, such as the loss of a parent.

Such babies are called spirit children or siri sirigu, and are thought to be bad omen for the community.

Below is a transcription of his documentary for Joy 99.7 FM’s Hotline.

I have come to the Upper East Region on an assignment, a very different assignment. The job has tight time frames. I’m rushing to meet deadlines.

I have come to the Upper East Region on an assignment, a very different assignment. The job has tight time frames. I’m rushing to meet deadlines.

I hear a stranger chatting with a friend on the streets of Bolgatanga. He mentions a Babies’ Home in the area.

The conversation reminds me of a story somebody once told me about this town and a very strange kind of orphanage.

Most children who end up in an orphanage have lost their parents. But in the Sirigu facility in Bolga, the children’s fate is much more tragic. If the child is born with deformities, the child is killed.

The first time I heard this story, I could hardly believe it. I’ve always lived in a community where great merry-making accompanies childbirth, no matter the condition of the baby or the mother.

So at first I didn’t pay too much attention to the story.

{They put the child on the hill and put plenty rocks on the child.}

Since coming to Bolgatanga I feel this story is following me. I see goose pimples all over my body and my eyes are heavy with tears when people tell me the details.

I have a very busy schedule. I tell myself I won’t have time to go to this place of horror. As I reach for my pillow one night to sleep, I can’t help myself. I make a firm resolution to travel to Sirigu the next morning no matter the consequences. It’s as if I have been possessed, I feel so uncomfortable.

I reach a friend at dawn the next day who agrees to take me on his motor bike to Sirigu. It takes about 45 minutes to drive from Bolgatanga to Sirigu and it’s not easy. The road is barely passable.

We have done only 10 minutes of the journey, and I have already regretted embarking on this trip. I don’t have a helmet. In the side mirror, I see my hair color has turned brown as if I’ve applied a dye.

I don’t have any protective cloth, so I’m shivering as if I’ve been beaten by heavy rain as I sit behind my friend on his bike.

But the story of those babies and a drive to understand the dark side of cultural practice keeps me going.

After 45 minutes of a bone-shaking journey, we finally reach Sirigu.

{Some come healthy, some come sick, some almost dying.}

At the Mother of Mercy Babies Home in Sirigu a Catholic Sister, a caretaker and a community leader are in front of the fading, brown iron gate of the home to welcome us. I look at the children and wonder what stories they would tell if they could find the words and exchange it with me. There are 16 babies in this 26-year-old home and the youngest is only two months old.

In an orphanage in Sirigu, in Ghana’s Upper East region. This Catholic Sister has dedicated her life to protecting babies and children. Now in 2018 the orphanage is being run by Afrikids.

The caretakers tell me the babies in the home are not considered ‘real’ human beings by their families. They have been cast out as evil spirits… either because they were born physically deformed or their mothers died during childbirth. And, according to an ancient cultural practice that survives in this area the babies must die to save the families from evil.

In some situations there were strange events at the time of their birth. All of the children except one, are motherless.

The caretaker, Sister Innocentia Depor tells me how some of the children are rescued and arrive on their doorstep.

{Because of the education, family members of the babies bring them themselves. The moment they get to know that the child can be termed a spirit child, they rush them here. So come very hefty, sick and weak.}

I decide to go to the nearby town to delve deeper into this story. Perhaps I will find some fathers or family members.

I meet the assemblyman for the area, Azokulgu Azotipelba, and he makes a shocking admission.

{it happened within our house, our family and within our community so I have witnessed it several times. And when that type of child dies, they don’t use a proper thing to carry him for the burial, they will take a rough mat and put the child there and hold it just like anything and go and throw it away. They normally don’t take the baby to the hill alive. They will use something like a stone, stick, or a cutlass to hit the child and kill him}

Once again, my entire body is shaking. My mouth is wide open and I’m close to tears as I visualize the events the Assemblyman is describing.

Trying to understand innocent blood being shed in the name of culture, I talk with an elder in the town, John Ayamaga. He takes time as he explains.

{when you give birth and the mother dies instantly, the myth is that it is the baby that has killed the mother so the child must also go so when there is no intervention, the baby is sent to the hill there for that rituals. If the child is born with some deformities either with some teeth or some of the hair being white, that child is termed a spirit child and that baby is not accepted in that community. We have a very big hill; they take them there and put a stone on that spirit child so that it will not get up again. The family will not fail to do that because they think if that baby has killed the mother, it can kill the rest of the family.}

I listen carefully to the stories of the people who have seen this horror first hand. I try to put myself in their shoes, to understand the fear and ignorance that leads to the slaughter of innocent children.

As I watch the kids of the Sirigu orphanage playing, I think of those who didn’t make here… Lying in shallow graves under a pile of stones on the hills in the distance.

Then a breeze blows through the window and this place of safety feels vulnerable. What if frightened family members hunted down these kids who have found refuge here. The assemblyman Azokulgu Azotipelba says this frightening possibility exists.

{At times the children will grow up to 10 or 15 years and they will still manage and go and kill that particular child. If a baby like this escape, the whole family and the entire community will come out and go and search and kill that baby. Because it is a culture for that community and the whole community believes that whatever the soothsayer says is for all so they have no reason to defy it.}

But despite these dangers the children will be discharged when they are three years old, according to the caretaker, sister Innocentia.

And, the local community has started taking advantage of the facility, bringing children who are not endangered but merely because they cannot afford to raise them.

{It was before that they don’t want the children that they always want to kill. But now with the education, they want their children but how to take care of them, very tiny, they prefer to bring the children here so that after three years when they can eat anything then they come for their child. When they bring the babies we always tell them not to come and throw the babies here like that. They should always visit them. And when they are bringing the babies, here, each child with a caretaker so that when the baby is discharged, he will have somebody he is familiar with. He will not feel like a stranger in somebody’s house.}

Poor people from the surrounding villages, outside Sirigu, have heard about the home and now bring their babies here because they are struggling to make ends meet. One child was recently brought from Bongo, a town in the Upper East Region. Little Marilyn as they’ve named her is only a month old but motherless. She is fortunate to have been spotted and saved by Hajia Mary Issaka, a midwife in-charge of the Anafubisi health center.

{Last week Friday we went to a community to run a clinic then we saw a pregnant woman holding this baby at the outreach point then we ask of the mother and she said the mother died at Bolga hospital. We ask what they were given and they told us that some people came to the funeral and donated some money and bought some lactogen and they are giving to the baby. So when we saw her, we knew that they cannot take care of the baby in the house so I sent this nurse to go the house and meet the community members and speak to the people about this orphanage. If they agree, we will arrange and bring the baby to Sirigu and they agreed.}

But little Marilyn is one of the more fortunate.

Everywhere I go in this town people have stories about baby killing that make my blood run cold.

{there are certain things they don’t even want to mention it. There was a community like that when a woman died after delivery and they gave the baby to another woman who died when there was an outbreak of CSM. And they are saying that it is the baby that has killed both the mother and the caretaker so they brought the baby out and knock the child on the tree and it died. So some of these things they are silent}.

The services of the Sirigu home is made possible by donations from foreign NGO’s like Friends of African Babies (FAB), based in the region.

Mary Kaglan is from Ireland and a member of the NGO. She tells me what motivated her organisation help the home.

{I think it was to see these sisters working so hard looking after so many babies thus the least we could do as we live in the area and that any help we could give them would be a bonus. The sisters of course take very good care of the babies so it is not that the case that the babies are looking after. But I think it is that people would be aware there is a home in Sirigu so people can visit and assist with the little they have}

But even with the assistance of the FAB NGO, sister Innocentia Apor and the staff here struggle to raise these children.

{The NHIS does not cover all the sickness so when you have a child that sickness surpasses the national insurance, it is difficult and to take a child like this, you would have to start the child with artificial food and all these are very costly. They are all the challenges. Right now we have one who has hydrocephalus and if it had not been FAB, it would have been difficult for us to take care of him. So medical wise it is a challenge}

The world is full of orphanages. And, I’ve done my fair share of stories about pain and suffering.

But the faces of the children of this place and the silent cries of the ones buried on the hill will remain with me for a long time to come.

Seth Kwame Boateng; for hotline in Sirigu.

Source: Modern Ghana, April 1, 2011

Upper East Region – Ghana