August 10 is World day against witch hunts.

During the past five years I have frequently posted on this sad topic. See e.g. the following posts: Witchcraft Persecution and Advocacy without Borders in Africa, earlier this year, as well as the following country-specific postings: DRC, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Zimbabwe.

Although not the main focus of this website I find it useful and necessary to draw attention to this phenomenon which is based on superstition, violates human rights and creates many innocent victims – not only elderly women and men but also children, just like ritual murders.

I wish to commend Charlotte Müller and Sertan Sanderson of DW (Deutsche Welle) – see below – for an excellent article on this topic. It’s an impressive account of what happens to people accused of witchcraft and victims sof superstition.

(FVDK)

World Day Against Witch Hunts: People With Dementia Are Not Witches

Published: August 4, 2023

By: The Ghana Report

August 10 has been designated World Day against Witch Hunts. The Advocacy for Alleged Witches welcomes this development and urges countries to mark this important day, and try to highlight past and contemporary sufferings and abuses of alleged witches in different parts of the globe.

Witchcraft belief is a silent killer of persons. Witchcraft accusation is a form of death sentence in many places. People suspected of witchcraft, especially women and children, are banished, persecuted, and murdered in over 40 countries across the globe. Unfortunately, this tragic incident has not been given the attention it deserves.

Considered a thing of the past in Western countries, this vicious phenomenon has been minimized. Witch persecution is not treated with urgency. It is not considered a global priority. Meanwhile, witch hunting rages across Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

The misconceptions that characterized witch hunting in early modern Europe have not disappeared. Witchcraft imaginaries and other superstitions still grip the minds of people with force and ferocity. Reinforced by traditional, Christian, Islamic, and Hindu religious dogmas, occult fears and anxieties are widespread.

Many people make sense of death, illness, and other misfortunes using the narratives of witchcraft and malevolent magic. Witch hunters operate with impunity in many countries, including nations with criminal provisions against witchcraft accusations and jungle justice.

Some of the people who are often accused and targeted as witches are elderly persons, especially those with dementia.

To help draw attention to this problem, the Advocacy for Alleged Witches has chosen to focus on dementia for this year’s World Day against Witch Hunts. People with dementia experience memory loss, poor judgment, and confusion.

Their thinking and problem-solving abilities are impaired. Unfortunately, these health issues are misunderstood and misinterpreted. Hence, some people treat those with dementia with fear, not respect. They spiritualize these health conditions, and associate them with witchcraft and demons.

There have been instances where people with dementia left their homes or care centers, and were unable to return or recall their home addresses. People claimed that they were returning from witchcraft meetings; that they crash landed on their way to their occult gatherings while flying over churches or electric poles.

Imagine that! People forge absurd and incomprehensible narratives to justify the abuse of people with dementia. Sometimes, people claim that those suffering dementia turn into cats, birds, or dogs. As a result of these misconceptions, people maltreat persons with dementia without mercy; they attack, beat, and lynch them. Family members abandon them and make them suffer painful and miserable deaths. AfAW urges the public to stop these abuses, and treat people with dementia with care and compassion.

Source: World Day Against Witch Hunts: People With Dementia Are Not Witches

And:

Witch hunts: A global problem in the 21st century

Image: Getty Images/AFP/F. Scoppa

Published: August 10, 2023

By: Charlotte Müller | Sertan Sanderson – DW

Witch hunts are far from being a thing of the past — even in the 21st century. In many countries, this is still a sad reality for many women today. That is why August 10 has been declared a World Day against Witch Hunts.

Akua Denteh was beaten to death in Ghana’s East Gonja District last month — after being accused of being a witch. The murder of the 90-year-old has once more highlighted the deep-seated prejudices against women accused of practicing witchcraft in Ghana, many of whom are elderly.

An arrest was made in early August, but the issue continues to draw attention after authorities were accused of dragging their heels in the case. Human rights and gender activists now demand to see change in culture in a country where supernatural beliefs play a big role.

But the case of Akua Denteh is far from an isolated instance in Ghana, or indeed the world at large. In many countries of the world, women are still accused of practicing witchcraft each year. They are persecuted and even killed in organized witch hunts — especially in Africa but also in Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Witch hunts: a contemporary issue

Those accused of witchcraft have now found a perhaps unlikely charity ally in their fight for justice: the Catholic missionary society missio, which is part of the global Pontifical Mission Societies under the jurisdiction of the Pope, has declared August 10 as World Day against Witch Hunts, saying that in at least 36 nations around the world, people continue to be persecuted as witches.

While the Catholic Church encouraged witch hunts in Europe from the 15th to the 18th century, it is now trying to shed light into this dark practice. Part of this might be a sense of historical obligation — but the real driving force is the number of victims that witch hunts still cost today.

Historian Wolfgang Behringer, who works as a professor specializing in the early modern age at Saarland University, firmly believes in putting the numbers in perspective. He told DW that during these three centuries, between 50,000 and 60,000 people are assumed to have been killed for so-called crimes of witchcraft — a tally that is close to being twice the population of some major German cities at the time.

But he says that in the 20th century alone, more people accused of witchcraft were brutally murdered than during the three centuries when witch hunts were practiced in Europe: “Between 1960 and 2000, about 40,000 people alleged of practicing witchcraft were murdered in Tanzania alone. While there are no laws against witchcraft as such in Tanzanian law, village tribunals often decide that certain individuals should be killed,” Behringer told DW.

The historian insists that due to the collective decision-making behind these tribunals, such murders are far from being arbitrary and isolated cases: “I’ve therefore concluded that witch hunts are not a historic problem but a burning issue that still exists in the present.”

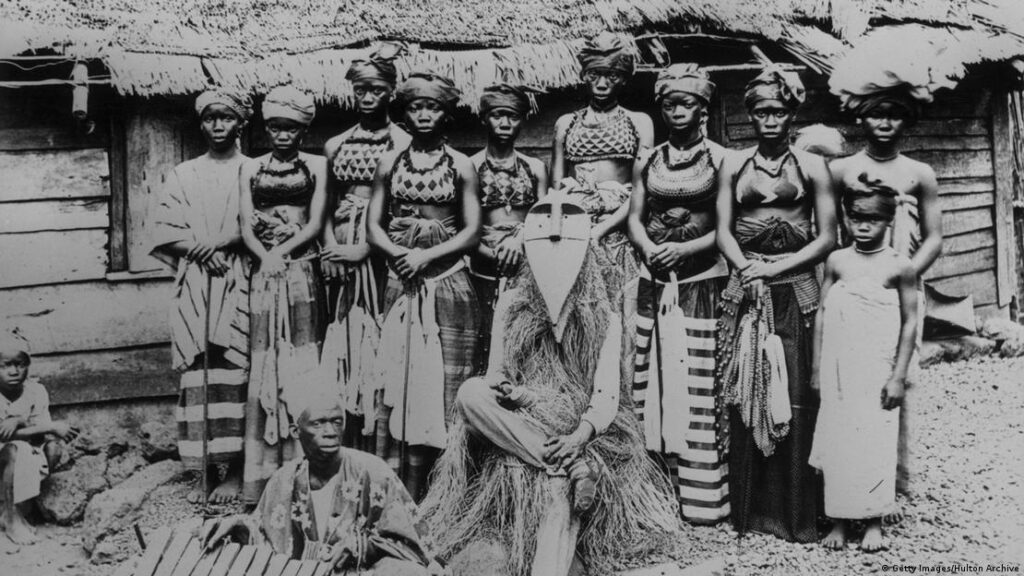

Getty Images/Hulton Archive

A pan-African problem?

In Tanzania, the victims of these witch hunts are often people with albinism; some people believe that the body parts of these individuals can be used to extract potions against all sorts of ailments. Similar practices are known to take place in Zambia and elsewhere on the continent.

Meanwhile in Ghana, where nonagenarian Akua Denteh was bludgeoned to death last month, certain communities blamed the birth of children with disabilities on practices of witchcraft.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it is usually the younger generations who are associated witchcraft. So-called “children of witchcraft” are usually rejected by their families and left to fend for themselves. However, their so-called crimes often have little to do with sorcery at all:

“We have learned of numerous cases of children suffering rape and then no longer being accepted by their families. Or they are born as illegitimate children out of wedlock, and are forced to live with a parent who no longer accepts them,” says Thérèse Mema Mapenzi, who works as a mission project partner in the eastern DRC city of Bukayu.

‘Children of witchcraft’ in the DRC

Mapenzi’s facility was initially intended to be a women’s shelter to harbor women who suffered rape at the hands of the militia in the eastern parts of the country, where rape is used as a weapon of war as part of the civil conflict there. But over the years, more and more children started seeking her help after they were rejected as “children of witchcraft.”

With assistance from the Catholic missionary society missio, Mapenzi is now also supporting these underage individuals in coping with their many traumas while trying to find orphanages and schools for them.

“When these children come here, they have often been beaten to a pulp, have been branded as witches or have suffered other injuries. It is painful to just even look at them. We are always shocked to see these children devoid of any protection. How can this be?” Mapenzi wonders.

Image: missio

Seeking dialogue to end witch hunts

But there is a whole social infrastructure fueling this hatred against these young people in the DRC: Many charismatic churches blame diseases such as HIV/AIDS or female infertility on witchcraft, with illegitimate children serving as scapegoats for problems that cannot be easily solved in one of the poorest countries on earth. Other reasons cited include sudden deaths, crop failures, greed, jealousy and more.

Thérèse Mema Mapenzi says that trying to help those on the receiving end of this ire is a difficult task, especially in the absence of legal protection: “In Congolese law, witchcraft is not recognized as a violation of the law because there is no evidence you can produce. Unfortunately, the people have therefore developed their own legal practices to seek retribution and punish those whom call them witches.”

In addition to helping those escaping persecution, Mapenzi also seeks dialogue with communities to stop prejudice against those accused of witchcraft and sorcery. She wants to bring estranged families torn apart by witch hunts back together. Acting as a mediator, she talks to people, and from time to time succeeds in reuniting relatives with women and children who had been ostracized and shamed. Mapenzi says that such efforts — when they succeed — take an average of two to three years from beginning to finish.

But even with a residual risk of the victims being suspected of witchcraft again, she says her endeavors are worth the risk. She says that the fact that August 10 has been recognized as the World Day against Witch Hunts sends a signal that her work is important — and needed.

Hunting the hunters — a dangerous undertaking

For Thérèse Mema Mapenzi, the World Day against Witch Hunts marks another milestone in her uphill battle in the DRC. Jörg Nowak, spokesman for missio, agrees and hopes that there will now be growing awareness about this issue around the globe.

As part of his work, Nowak has visited several missio project partners fighting to help bring an end to witch hunts in recent years. But he wasn’t aware about the magnitude of the problem himself until 2017.

The first case he dealt with was the killing of women accused of being witches in Papua New Guinea in the 2010s — which eventually resulted in his publishing a paper on the crisis situation in the country and becoming missio’s dedicated expert on witch hunts.

But much of Nowak’s extensive research in Papua New Guinea remains largely under wraps for the time being, at least in the country itself: the evidence he accrued against some of the perpetrators there could risk the lives of missio partners working for him.

Not much has changed for centuries, apart from the localities involved when it comes to the occult belief in witchcraft, says Nowak while stressing: “There is no such thing as witchcraft. But there are accusations and stigmatization designed to demonize people; indeed designed to discredit them in order for others to gain selfish advantages.”

Maxwell Suuk and Isaac Kaledzi contributed to this article.